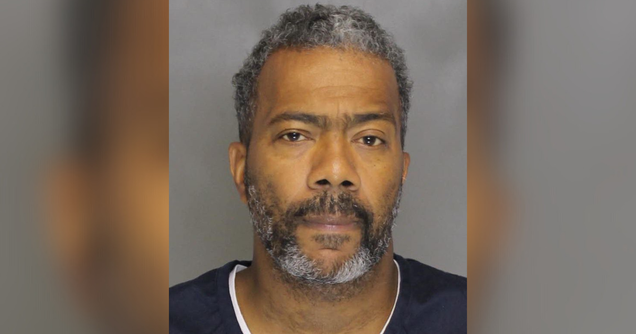

Junia Joplin — June to her friends — is a pastor near Toronto who recently came out as trans to her congregation in the form of a sermon. | Jah Grey for Vox

Junia Joplin — June to her friends — is a pastor near Toronto who recently came out as trans to her congregation in the form of a sermon. | Jah Grey for Vox

The church has not easily embraced those like Junia Joplin. Could telling her story help her keep her job?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

When she was 11, at a Christian summer camp, on an island, in the middle of a lake in upstate New York, Junia Joplin — June to her friends — realized two things: She wanted to be a minister, and she wanted to be a girl.

She realized she wanted to be a minister because, well, it was a church camp. But she knew she wanted to be a girl because girls were separated on the other side of the island. And June knew, on some subconscious level, she was on the wrong side of that island.

“There wasn’t a day when I was 11 that God said, ‘Oh, hey, June, by the way, there’s something I want you to do,’” she says. “It’s less like a Post-It note that shows up on your door one day and more like this transmission that you keep turning the dials on for the rest of your life. That’s also the way I think about gender. So many of us can say that they had inklings [about their gender] at 4 or 5, 6 years old. ... Some of us it’s not as clear. It’s a lot more faint. But it’s always there.”

“I want to be a minister” and “I want to be a girl” weren’t revelations that could be pursued simultaneously, at least not in 1990 in rural North Carolina, where June grew up. She had to pick one door or the other.

“I came home from camp realizing that some profound things had happened to me over the course of that week. There was part of it that I could tell people and act on and receive accolades, even. And there was part that I couldn’t ever tell people or act on,” she says.

She chose the door marked “minister,” because, she thought, wanting to be a girl was a dream for other people. She grew up, and went off to seminary in Richmond, Virginia. She started preaching there. She was really, really good at it.

Almost from the start of her career, June was talked about as someone who might rise through the ranks of Baptist churches to more high-profile jobs.

“The combination of American Christianity and late-stage capitalism has created a sifting effect where there are $6-an-hour pastors and six-figure pastors. There’s not a lot in between,” June says. And as a white, seemingly cis male with a wife and children, June was fast-tracked to professional success.

Elizabeth Lott, a friend and coworker from those Richmond days, remembers joking about how June would join the “good-old-boy network,” the pastors who glad-handed their way to positions of leadership, perhaps benevolently nudging people toward acceptance of those who were not straight, white, cis, and male — but only nudging.

Lott could see something else in June. “I just knew that there was a dark sadness that couldn’t be shaken, and because we were close, I knew there were things that just didn’t line up,” she says.

When June was 35, she moved to Canada to take over Lorne Park Baptist Church in Mississauga, Ontario, a suburb of Toronto. When she left for Canada, she told people she was trying to escape the race to the top of her denomination. But if she had landed in Chattanooga, Tennessee, instead of Mississauga, she says, what happened next might never have.

In 2017, she became an assistant club hockey coach and had to undergo training on gender identity. And that was when she remembered her long-ago choice to walk through just one door, and realized both of those doors were her. She felt God’s presence in that moment, when she knew both what she had to do and what it could mean for her career. She might be tossed out of the church and rejected.

But opening the door she had long avoided was worth the potential sacrifice. So in 2018, Junia Joplin came out to herself. And she stepped into the wilderness.

“You and I both grew up during the height of the AIDS crisis,” June, 41, tells me when I talk with her in May. “When I was a teenager, after the point that I developed the persistent wish that I would be a girl, my pastor in a sermon on Sunday morning said that he thought, like, all gay people should be rounded up and put on an island somewhere.” To June, growing up in that environment, transition felt like something for other people. It was something for people in cities like New York or Los Angeles, not for a kid at a fundamentalist Baptist church in North Carolina.

June and I both grew up in the conservative Christian Church of the 1990s. It made us put up walls around our true selves as we chased an ill-fitting masculinity. Bonding over this was one of the early cornerstones of our friendship.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20042670/GettyImages_1192239201.jpg) Boston Globe via Getty Images

Boston Globe via Getty Images

For most of our lives, the thought of the church accepting queer identities seemed impossible. But in 2020, the church might have reached a point where a trans woman minister can be accepted. Maybe. (The Baptist denominations to which June and other ministers quoted in this article belong are distinct from the Southern Baptist Church, one of the most conservative denominations in the United States.)

“Most religious groups have moved to support marriage equality, to support nondiscrimination laws that support transgender people,” says Robert Jones, the founder of the Public Religion Research Institute, which conducted a survey on Christian denominations’ views on trans identities in 2019. “White evangelical Protestants are the only group where there’s a majority opposition to marriage equality today. Every other religious group is either divided or supportive.”

This shift is the natural culmination of decades of church history. The explicitly queer-affirming Metropolitan Community Church denomination began in Los Angeles in 1968 and quickly spread worldwide. The Episcopalian Church named a gay man as a bishop in 2003, which also led some individual churches to split off from the denomination. And both the Lutheran and Methodist churches have faced denominational schisms over accepting LGBTQ people in the past few years.

“So often, progress comes two steps forward and one step back. But even if you look at the most conservative evangelical churches, there are cracks starting to form,” says Jeff Rock, pastor of Toronto’s MCC, which June attends on Sunday evenings.

“I think the Church with a capital-C needs to be public and vocal and unwavering about its support for queer and trans people, labeling our experiences as holy, proclaiming us beloved children of God,” says Rev. Erica Saunders of Peace Community Church in Oberlin, Ohio. She’s only the second trans woman ordained into the Alliance of Baptists denomination and the first to be ordained when already out. “That’s going to include welcoming us into all levels of power, administration, polity — not just saying, ‘You can come in,’ but allowing us to be part of life in all its abundance.”

The question of what happens after churches embrace queer folks, however, remains very much open. The Christian Church — especially the Evangelical Church — has been one of the foremost opponents of LGBTQ rights, and evangelicals continue to push regressive trans policies. Is there any way to have healing in the church, even with pastors like June, pastors who know how badly the church has hurt people like her?

“In the Christian tradition,” June says, “God is said to be especially present in the wilderness. You’re not here. You’re not there. You’re in between. You’re in between for decades, wandering like the children of Israel in the story of the Exodus, and God is there in a special way. Jesus himself spent time in the wilderness. The Gospel of Luke, for the whole center section of the book, keeps saying, ‘And he was on his way to Jerusalem.’ But he’s not there yet. He’s not where he was. He’s not where he’s going. He’s just on the road.”

June is not where she’s going yet, either. By coming out, she might lose more than her job. She’s trying to become a Canadian citizen, which will be made trickier if she’s suddenly unemployed. Canada’s nationalized health care covers trans care, but she risks losing her hormones and her access to potential surgeries if she has to leave. She is going to lose her marriage, because her wife, though incredibly supportive, is also straight. (They are separated.) She might lose even more than that.

And yet here she is.

I spoke with June on the evening of Saturday, June 13, less than 12 hours before she would leave her current wilderness and enter another entirely, by coming out in the form of a sermon. She’s been asked several times by the clergy she’s trusted enough to confide in why, precisely, she wanted to come out in a sermon, rather than telling her church’s leadership board, then going on up through the denomination’s official chain of command to let everyone know she would be transitioning. Only then would she come out, possibly in a sermon, if everybody was cool with that.

The truth is that this plan is June’s best chance at keeping her job. When I asked her why she wasn’t going through official channels, she rattled off the names of several trans women pastors who tried to do so and were summarily removed from their jobs, before they could become a news story and create an uncomfortable situation for their churches.

So here I am. This is now a news story. You are part of June’s story, too, her bulwark against an easy dismissal.

I want to believe she will change minds. The sermon is an exquisite piece of writing, and when I read it shortly before she would first deliver it, I had every faith that June would deliver it beautifully. But it will be impossible to escape the pull of what comes next, and there’s really no way to know if what comes next will be losing her calling or finding a portal to something new.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20043417/GettyImages_1065487754.jpg) Toronto Star via Getty Images

Toronto Star via Getty Images

The Bible is full of gender-nonconforming people, if you know where to look for them.

“We don’t teach stories like Deborah, the warrior who went out to battle in Judges, or Joseph, the gender-nonconforming kid with this coat of many colors, in Sunday school, so people never learn them,” says Austen Hartke, head of Transmission Ministry Collective and author of Transforming: The Bible and the Lives of Transgender Christians. “You grow up thinking that gender-expansive or gender-nonconforming folks don’t exist in our tradition. They definitely do.”

Or consider another case. In the book of Romans, chapter 16, verse 7, Paul, Christianity’s most famous early convert, says hello to a couple of prominent friends:

Greet Andronicus and Junia, my fellow Jews who have been in prison with me. They are outstanding among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was.

Junia is a mystery. The name “Junia” is a woman’s name in Greek (the language in which the New Testament was written), but the idea that a woman could be an apostle seemed a heresy to many long after St. Junia had died.

So she was given the male name “Junias” in either the late second or early third century. Junia was thought of as a man for almost the entirety of church history. Though efforts to restore her womanhood trace back to as early as the 1500s, the translation that seems to have solidified Junia as the only female apostle mentioned in the Bible only arrived in 1998. Imagine being such a faithful steward of the early church that you are mentioned in the Bible, by Paul, no less. And then imagine the church stripping your identity from you — a woman, hiding in plain sight, under the guise of a man.

So when Junia Joplin first preached as herself in 2018 while visiting Erica Saunders — who had impulsively asked June to deliver a sermon — she realized she had to pick a new name. The perfect one was waiting for her. She had been hiding in plain sight, too.

I started talking to June in the spring of 2019, when I stumbled upon the secret Twitter account she had set up to talk about her transition without outing herself publicly. (I was browsing Twitter using the secret Twitter account I had set up to talk about my transition without outing myself publicly.)

What drew me to her was the way she talked about how coming out was going to ruin her life and probably cost her her job. Many other members of trans Twitter insisted to her that, no, she would be fine! The world was more accepting than ever before!

This relentless positivity drove us both up the wall. We were both sure our jobs would be complicated or lost entirely after we came out (though on Twitter, June remained cagey on what she actually did). We both grew up in rural areas where we knew gossip about our transitions would run rampant. We both feared what our ultra-conservative parents would say.

Predictably, June and I hit it off.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20038721/005.jpg)

And then I came out, and I was fine. The world was more accepting than ever before. It felt simultaneously like finally emerging from the ocean’s depths into fresh air and like the cruelest of jokes. For the vast majority of people, all I had to do to claim my womanhood was tell them how deeply I knew I was a woman? Why hadn’t I done it long, long ago?

I told June as much over Twitter direct messages, and finally, we were close enough friends that she revealed what she did for a living, and I thought, “Oh, she’s going to lose her job.”

The church had been enormously important to me as a child. I had been a fervent believer, certain that God had plans for me. But when I reached adulthood, I left. I didn’t really know why. I kept saying that I would come back, and I was afraid of hell long after I stopped believing in it. But adolescence had stripped away my faith. My body no longer made sense to me, so nothing else did either. I couldn’t go back. To step into a church was to step into the wilderness.

That’s not an uncommon experience for trans people of faith. “I would ask to be saved, but I wouldn’t feel anything,” said Rev. Saunders. “What was going on there was that I wasn’t connected to my own body, and I wasn’t authentically myself because I was trying to hide who I was, even if subconsciously.”

In his 1979 book The Orthodox Way, the Orthodox bishop Kallistos Ware argues that God does not find us but that we, instead, find God by finally coming to understand ourselves, to see the ways in which we are made in God’s image and better know the almighty’s presence in our own lives. You cannot find God, in other words, until you have found yourself. In this way of believing, for a queer person to embrace their identity is to embrace what is godly in them.

After I came out, I heard that voice again. “Come home,” it said. So I started going to church, joining a denomination (Episcopalian) that accepted me as I was. I found kinship there. I found an idea of faith bigger than the limits humans place on it. I found home.

Maybe my rediscovery of the church played a part in why I started talking to June more often. We talked about faith, about our upbringing, about our lives. We were two people who should never have found each other, if only due to geography, and yet here was some force beyond us, guiding us together. In strictly rational terms, it was our shared trans identity. But I no longer think solely in strictly rational terms.

A little over five hours before she was to preach the sermon where she would come out — 5 am her time, 2 am mine — I realized that June was also awake. When we hopped on a Zoom call, she was teary. “I’m just thinking about all the people who didn’t get to do this,” she told me, all those trans Christians who never got to live their lives, who got lost in that wilderness within the church’s doors.

It was early for June, late for me. I didn’t really know what to say, so we made small talk. We compared tattoos. We prayed together. And then she had to get ready.

June’s coming-out sermon was streamed to her congregation over YouTube, which means so many of her trans siblings were able to watch, too, including me, bleary-eyed, up too early in Los Angeles. Purely on a structural level, the sermon was one of the best I’ve ever seen. It provided an entire lesson from the New Testament about embracing truth before June shares her own.

But will it be enough? There are a few trans ministers in the world — mostly sprinkled here and there throughout North America — but very, very few. And often, the act of a pastor coming out as LGBTQ in any fashion is seen as a disruption that merits dismissal.

“I know how local congregations think — ‘We love her, but not everybody in the church can agree with this. It will split the church. Therefore, we will sacrifice her,’” said Rev. Donnie Anderson, who came out as trans at 69, while working for the Rhode Island Council of Churches. “That’s my best guess. I hope and pray that I am so wrong. There are few things in my life I’ve wanted to be wronger about.”

Anderson retired from her job with the council. Her new ministerial position in Provincetown, Massachusetts, is only a part-time job. June says she believes that might be her best-case scenario: She is removed from her full-time position but finds part-time work in another church. She supplements that income with a different job. But that will be very different. It won’t be what she felt called to do.

“After 30 years of choosing vocation over gender, now I have to choose gender over vocation. It’s not a scenario where I get to be a full person in either way,” June says. “I don’t want to be in a position where some denomination can say, ‘We hired this trans woman. We’re paying her for 20 hours a week. She can’t pay her rent, but aren’t we inclusive?’ I can’t say that I wouldn’t do that, just because what choice would I have? But I don’t want to be a prop. I don’t want to be a novelty.”

The church has always been a patriarchal institution, which extends to trans identities, in harmful ways. When a trans man minister comes out to his congregation, he is much more likely to keep his job than a trans woman minister who comes out to her congregation.

There are a small handful of exceptions throughout North American Protestantism, like Rev. Saunders. Her first day of living full time as a woman was also her first day of divinity school. She has a full-time pastoral job. She is only about 15 years younger than June, but she somehow got to choose both doors. She is the best-case scenario. Yet Saunders found her job when she was already living as her authentic self. It’s a far different struggle when a congregation already has a relationship with a minister that is suddenly, radically changed.

June’s friend, Rev. Elizabeth Lott, says that pastors are often more progressive than their congregations, something that often manifests in those pastors pulling their punches with sermons that tiptoe right up to endorsing social justice movements, then back away from the cliff’s edge. Those pastors, often white, straight, cis, and male, have the luxury of distance from the need for that social justice. June won’t.

“Everything [changed] for June on Sunday, but it may be that that opens up something for her, because once she’s able to inhabit who she fully is, she’s going to be able to free other people to do the same,” Lott said. “I am hopeful for her. She’s been pretty focused on the fallout, and yeah, there’s gonna be some fallout.”

The aftermath of June’s sermon offered inconclusive proof of what might happen to her next. She received an outpouring of support from parishioners — including a few she hadn’t quite expected to be in her corner. Friends she hadn’t heard from in years reached out to her, too, to share their love and acceptance.

But she also received a rather terse email from her church’s leadership council saying “no decisions have been made yet.” At least, June says, they got her name and pronouns right.

I cannot describe to you how much this sermon meant to me and to the other trans Christians I know. June, knowing that her sermon would be seen by so many queer Christians around the world, since it’s on YouTube, pitched its last section to those very believers:

In particular, I want to proclaim to my transgender siblings that I believe in a God who knows your name, even if that name hasn’t been chosen yet. I believe in a God who calls you a beloved daughter even if your parents insist you’ll always be their son. A God who blesses you and gives you a home even if you’re not welcome in the place you used to call home. A God whose relentless creativity invites you to become who you were created to be, even if you have to risk everything to do it.

I grew up not with an idea of myself but with a negation of myself. I was formed not by the contents of my heart but by the boundaries others set for me. I was less a person than a collection of rules, rules that I struggled to shrug off even after I left the church. I could not conceive of myself as transgender because long ago, I had been told that being trans meant belonging to the wilderness. But what if I had heard June’s words as a child, or as a teen? Who might I have been?

There’s a story I thought I knew until June showed me something hiding inside of it, right in plain sight.

In the book of Genesis, God commands Abraham to kill his son, Isaac. Abraham and his wife, Sarah, were supposed to be too old to have a child until God gave them Isaac. God’s command is an incalculable horror for Abraham. Still, he obeys, preparing a human sacrifice. At the last moment, God stays Abraham’s hand. God was merely testing Abraham. Isaac is saved. All is well in the end.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20038725/003.jpg)

I’ve always heard this story told as one about obedience. Abraham did exactly what God said, and he was blessed, first with Isaac and then with the thousands of generations that followed. But how far is that obedience supposed to stretch?

It was June who told me about the story’s aftermath. After Abraham nearly sacrifices Isaac, the story cuts forward several years to Sarah’s death. She has moved hundreds of miles away and is no longer married to Abraham. Isaac left his father, too. Abraham has married another wife, but she is not Sarah. He has had many other children, but they are not Isaac. In his pursuit of God’s will, he has lost everything.

I am sure some will say Abraham’s sorrow is a victory. He was willing to follow God even to the utter devastation of everything he cared about, and he was rewarded for it. But was he? Can we call that a reward? And who are you in this story? Abraham, following orders? Isaac, breaking for freedom? Sarah, at a loss? God, ordering the inconceivable? Which door do you walk through?

Here is what I think: We are meant to see ourselves in all four of these people, because we have been and will be all four of them. We are, all of us, in the wilderness. There are no maps for these empty places. But there are compasses.

It is not a mistake that acknowledging my transness brought me back to the church; it is also not a mistake that June acknowledging her own might cause her to be cast out. Queer people turn themselves into husks every day trying to be seen by the faith of their youth. Doing so is not a noble sacrifice. God never, ever stays our hand.

Maybe, then, we find meaning in coming together. June has said, from the moment I met her online, that in some other life, we would not have been friends. Our lives are so very different. But because we shared this quiet whisper of an inner voice that told us we were not done discovering ourselves, our compasses pointed toward each other.

Now that she’s spoken her truth at last, others might hear her words above the wind. We might still find each other in this wide and empty space. The wilderness grows a little smaller every day.

Emily VanDerWerff is Vox’s critic at large. Read her essays here and here.

Jah Grey is a self-taught photographic artist primarily focused on portraiture. He is based in Toronto, Ontario.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/3eEK8ye