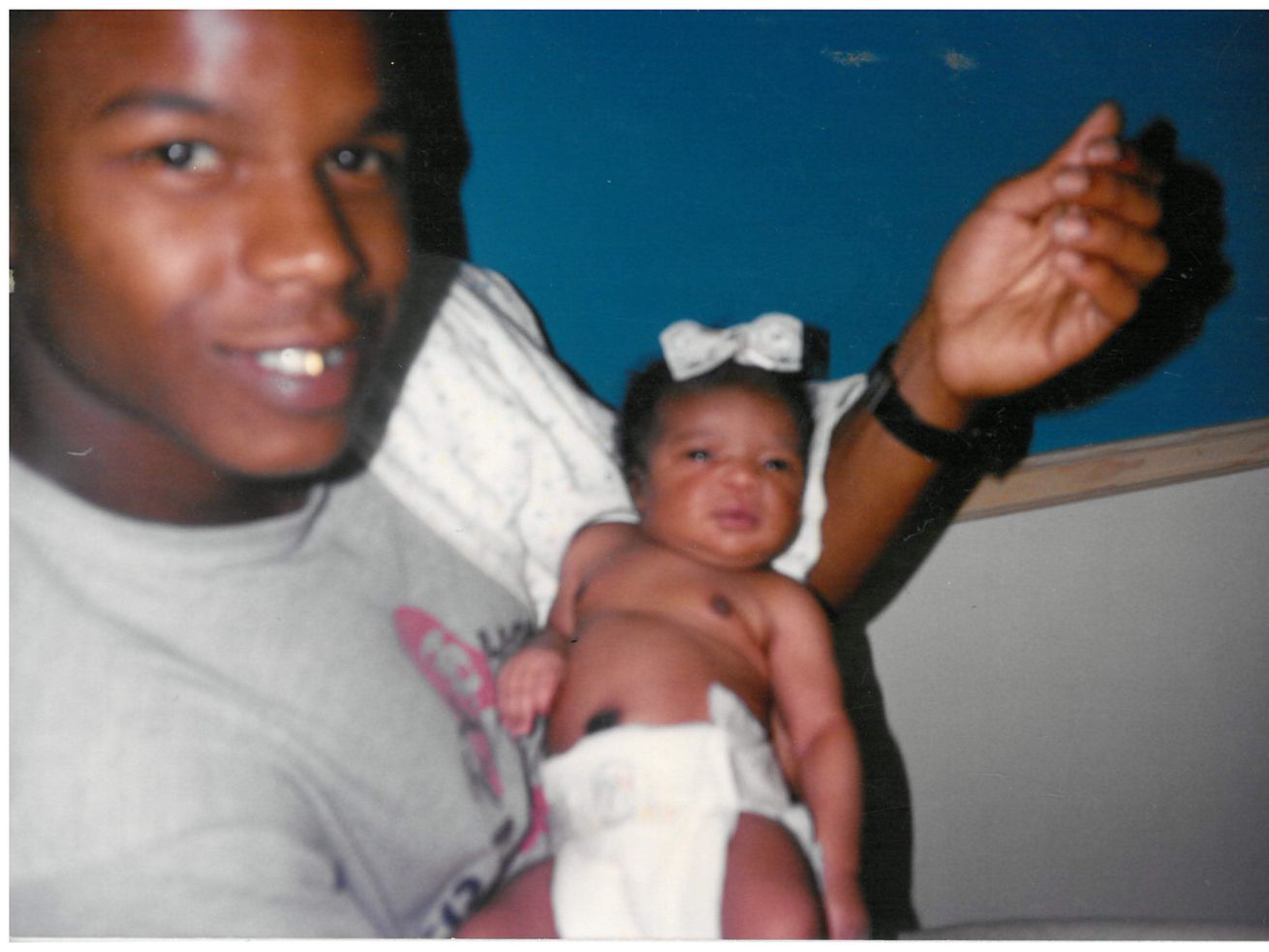

My mother took a photo of my father, Paul, holding me during my first doctor’s visit in 1993. This is our only photo together. | Courtesy of Montinique Monroe

My mother took a photo of my father, Paul, holding me during my first doctor’s visit in 1993. This is our only photo together. | Courtesy of Montinique Monroe

It took his resurfaced racist posts for me to tell my father’s story.

A familiar numbness occupied my body when I learned George Floyd’s 6-year-old daughter, Gianna, had asked her mom why people were saying her daddy’s name.

I was relieved to know she wasn’t given the graphic details of Floyd’s death. But I knew one day, she’d find out exactly what happened and would be forced to face the trauma that comes with losing a father to police violence. I was once in her shoes.

When I was just 4 months old, my father was killed by a white police officer. To protect my innocence, my family spared me the truth until I was around Gianna’s age. I’ll never forget how fast my breath escaped my body when I learned what really happened. I was confused and unable to decipher what it meant that the police, the people I’d grown up thinking were here to protect me, had taken my father’s life. My views of safety were shattered. Beyond that, I couldn’t bring my father back. I was left with a space that would remain unfilled.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21714533/DadsWake.jpg)

As I grew older, this emptiness became fear, avoidance, anxiety, anger, and sometimes self-pity. Today, it fuels me. He is unable to speak for himself, so I’ll speak for both of us.

Steven Deaton forever changed my life when he shot and killed my father 27 years ago on April 15, 1993. Deaton, who’d been an officer with the Austin police for two and a half years, was dispatched to the scene of an alleged armed robbery with two other officers. When they arrived at Quail Run Apartments, they suspected my 23-year-old father, Paul Monroe, was involved.

According to an incident report my family obtained from the Austin Police Department, the officers approached my father as he walked toward them. They gave him directions to drop a duffle bag. He dropped the bag. After he was told to get on the ground, Deaton shot him in the abdomen.

Another officer handcuffed my father as he lay helpless in his own blood until the ambulance came. My father asked for water but his request was denied. When EMS arrived, they had to request he be unhandcuffed to treat him. He was rushed to the hospital and after losing too much blood, he died in the ICU the next morning. The medical examiner ruled his death as a homicide. Eleven days after Deaton fatally shot my father, a Travis County grand jury decided against indicting him, claiming the shooting was justified.

“Until the moment I pulled the trigger, it was another police call,” Deaton said in a 1993 Austin American Statesman article about killing my father. “It’s something I’m going to have to think about for the rest of my life.”

Deaton may have been stuck with the memory, but I’ve had to live with the actual consequences of his actions. I’ve lived my whole life without my dad. Twenty-seven birthdays, countless holidays, basketball games, father-daughter dances, and graduations — that’s what Deaton took from me the day he fired the bullets that claimed my father’s life.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21714542/10_16_2007_2.jpg)

I’ve longed to say “Dad” and hear a reply from my father, to know the sound of his voice, embrace him, hear him laugh, or simply just see his face. But unfortunately, all I have to rely on is my imagination and frequent reminders from my family about the amazing father he would’ve been if he was here.

My only way of knowing him has been through the eyes of others. His friends and family say he was highly respected in his East Austin community, taking care of youth who didn’t have families. He was a funny guy and a hustler who would give the shirt off his back at the drop of a dime. His proudest accomplishment was being my father. He called me his “star.” Knowing this gives me endless comfort and happiness I can’t explain.

Yet, when I think about him, I always find myself drifting back to the fear he must have felt in his final moments. His last recorded words — “you shot me, I need water, I can’t see, I can’t feel my legs” — show he was scared and confused.

His life was more than tragedy and death, but for me the most unforgettable image of my father is of him lying in a casket.

I stumbled upon this photo as a teen who spent hours occupied in storage closets, fumbling my way through boxes and boxes of family scrapbooks and photo albums, reflecting on happy family memories. One day, I found an album dedicated to my father, chronicling his life from birth to death. Scattered among his memorial photos were news clips: “Man’s death brings confusion” and “When police officers fire, lives are changed forever.” I remember reading and re-reading Deaton’s chilling words — “The thing about the shooting, it was instinct, it was what the police academy trained you for” — over and over again before closing the album. I didn’t visit the album again until years later.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21714555/Image_28_.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21729997/mnm_dadsstory2190__1_.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21714553/DadFuneral_2.jpg)

But I had always had a desire to tell my father’s story — in fact, I chose to become a journalist so I could. Working for my university’s independent student-run newspaper in 2014, I’d given myself an assignment to cover the death of 18-year-old Michael Brown, who was fatally shot by white police officer Darren Wilson, in Ferguson, Missouri.

I was motivated by the national anger over police brutality, hopeful that the movement could spur outrage about the way my father was executed too. However, I knew that to the mainstream media nothing was newsworthy about a Black man who was killed by a white police officer decades ago. It’s hard to convince an industry that is so heavily driven by, and consumed through, a white lens of the importance of telling stories like mine outside of fires, shattered glass, and national unrest.

But five years later, in August 2019, I received a text message from my mother with a link to an article with the headline “Texas sheriff who stars on reality show fails to publicly address sexist images posted on Facebook by one of his top officers.” “Isn’t this the cop who killed your father?” her text read.

I sped to the next red light and frantically scrolled up and down, past the graphic images throughout the story. It was as eerie as it was gut-wrenching. The article, from the Southern Poverty Law Center, reported that Deaton had shared racist photos in a Facebook post depicting a Black football player figurine lying in a pool of blood, his knees amputated by a white Santa elf doll with a chainsaw, while an American flag dangles above them. Deaton’s post, a reference to Colin Kaepernick kneeling during the national anthem to protest police brutality against Black people, was captioned: “And here’s the start…...Our Patriotic elf grew angrier all season. He finally snapped and decided to show the NFL how he goes about taking knees for not standing during our national anthem. #thankavet.”

Here was my father’s killer so boldly and fearlessly expressing his discontent with protests of police brutality. And that wasn’t even the only sickening post he had shared. Other photos depicted elf dolls sexually assaulting Barbies. A survivor of sexual assault who lived in the city his department serves reported she was retraumatized by his posts.

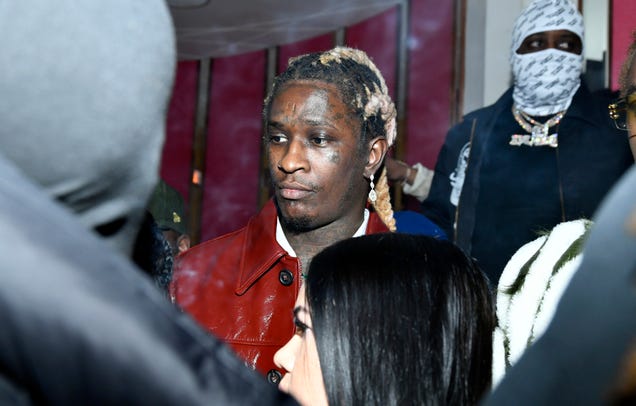

As I looked at Deaton’s grin in the photo at the top of another news article, I too was blanketed by a sense of anxiety. This familiar feeling surfaces at the sight or sound of anything involving law enforcement — a repercussion of losing a loved one to police violence. It comes up during the simplest of times, while driving or even walking past a police officer in public. I tell myself: Don’t speak, don’t make eye contact, don’t make any sudden moves. An officer might “fear for their life,” and I’ll be next.

But I couldn’t help but notice that in the coverage of the Facebook posts there was no reporting on the fact that he’d killed my father. If my father didn’t make it into the news, what other countless stories might not have been reported?

Like many officers who kill and get away with it, Deaton’s career thrived after he shot my father. He stayed with Austin police for 26 years, rising to the rank of assistant chief. Despite other widely publicized inappropriate behavior and departmental violations, he was able to move to Williamson County Sheriff’s office, where he served until he resigned after the Facebook posts.

Seeing my father’s killer share imagery and rhetoric that encouraged violence against Black people confirmed my belief about his lack of remorse and concern for the life he took from me 27 years ago. It confirmed my belief about his complete removal from the pain and suffering of victims of police brutality and their families. It shows what likely was in his heart the moment he fired the bullets that killed my father, and it proved what my family and I have believed all along — he murdered my father.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21714550/DadsGrave.jpg)

I’ve fought for so long to tell my father’s story. Unfortunately, there are so many others like me who never will. There are countless children who were sat down and told their father, or their mother, was killed for reasons they couldn’t quite comprehend, unaware that this truth would impact them throughout their entire lives.

I’m not sure I have the right words to comfort them. But I know this much: Our stories matter. Every day when we wake up and look in the mirror, we see a reflection of the parents who were taken from us. We are their legacies.

Montinique Monroe is a photojournalist in Austin, Texas.

Will you become our 20,000th supporter? When the economy took a downturn in the spring and we started asking readers for financial contributions, we weren’t sure how it would go. Today, we’re humbled to say that nearly 20,000 people have chipped in. The reason is both lovely and surprising: Readers told us that they contribute both because they value explanation and because they value that other people can access it, too. We have always believed that explanatory journalism is vital for a functioning democracy. That’s never been more important than today, during a public health crisis, racial justice protests, a recession, and a presidential election. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive, and advertising alone won’t let us keep creating it at the quality and volume this moment requires. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will help keep Vox free for all. Contribute today from as little as $3.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/30VpyoD