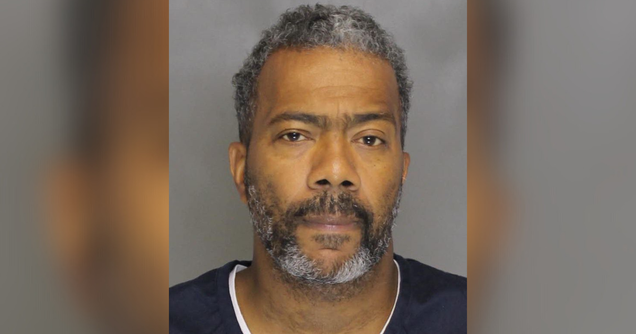

President Donald Trump greets Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch as Supreme Justice Brett Kavanaugh looks on ahead of the State of the Union address in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives on February 04, 2020 in Washington, DC. | Mario Tama/Getty Images

President Donald Trump greets Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch as Supreme Justice Brett Kavanaugh looks on ahead of the State of the Union address in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives on February 04, 2020 in Washington, DC. | Mario Tama/Getty Images

The Supreme Court’s new decision on Wisconsin mail-in ballots threatens a century of voting rights law.

The Supreme Court just handed down an order in Democratic National Committee v. Wisconsin State Legislature determining that a lower federal court should not have extended the deadline for Wisconsin voters to cast ballots by mail.

The ruling, which was decided by a 5-3 vote along party lines, is not especially surprising. The lower court determined that an extension was necessary to ensure that voters could cast their ballot during a pandemic, but the Court has repeatedly emphasized that federal courts should defer to state officials’ decisions about how to adapt to the pandemic. Monday night’s order in Democratic National Committee is consistent with those prior decisions urging deference.

What is surprising, however, is two concurring opinions by Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, each of which takes aim at one of the most foundational principles of American constitutional law: the rule that the Supreme Court of the United States has the final word on questions of federal law but the highest court in each state has the final word on questions of state law.

This division of power is implicit in our very system of government. As the Supreme Court has explained, the states and the federal government coexist in a system of “dual sovereignty.” Both the federal government and the states have an independent power to make their own law, to enforce it, and to decide how their own law shall apply to individual cases.

If the Supreme Court of the United States had the power to overrule a state supreme court on a question of state law, this entire system of dual sovereignty would break down. It would mean that all state law would ultimately be subservient to the will of nine federal judges.

Nevertheless, in Democratic National Committee, both Gorsuch and Kavanaugh lash out at this very basic rule, that state supreme courts have the final say in how to interpret their state’s law, suggesting that this rule does not apply to most elections.

They also sent a loud signal, just eight days before a presidential election, that long-settled rules governing elections may now be unsettled. Republican election lawyers are undoubtedly salivating, and thinking of new attacks on voting rights that they can launch in the next week.

A potentially seismic reinterpretation of American election law

As Gorsuch notes in his concurring opinion, which is joined by Kavanaugh, the Constitution provides that “the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.” A separate constitutional provision provides that “each State shall appoint” members of the Electoral College “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct,”

According to Gorsuch, the key word in these constitutional provisions is “Legislature.” He claims that the word “Legislature” must be read in a hyper-literal way. “The Constitution provides that state legislatures — not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials — bear primary responsibility for setting election rules,” he writes.

The implications of this view are breathtaking. Just last week, the Supreme Court split 4-4 on whether to overturn a Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision that also would have allowed some mailed-in ballots that arrive after Election Day to be counted. Both Gorsuch and Kavanaugh were among the dissenters, though because there were no written opinions, neither explained why they would have thrown out the state supreme court’s decision.

We now know why. Based on Gorsuch’s reasoning in Democratic National Committee, it’s clear that both he and Kavanaugh believe the Supreme Court of the United States may overrule a state supreme court, at least when the federal justices disagree with the state supreme court’s approach to election law.

That is, simply put, not how the balance of power between federal and state courts works. It’s not how it has ever worked.

Nor is it correct that the word “legislature” should be read in the hyper-literal way Gorsuch suggests. For more than a century, the Supreme Court has understood the word “legislature,” as it is used in the relevant constitutional provisions, to refer to whatever the valid lawmaking process is within that state. As the Court held most recently in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015), the word “legislature” should be read “in accordance with the State’s prescriptions for lawmaking, which may include the referendum and the Governor’s veto.”

But Gorsuch’s opinion suggests that this longstanding rule may soon be gone (again, as he put it, “state legislatures — not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials — bear primary responsibility for setting election rules”). State supreme courts may lose their power to enforce state constitutions that protect voting rights. State governors may lose their power to veto election laws, which would be a truly astonishing development when you consider that every state needs to draw new legislative maps in 2021, and many states have Republican legislatures and Democratic governors.

The return of Bush v. Gore

Kavanaugh, for what it’s worth, takes a slightly more moderate approach in his concurring opinion. The Supreme Court of the United States, he writes in a footnote to that opinion, may overrule a state supreme court when the state court defies “the clearly expressed intent of the legislature” in a case involving state election law.

Just how “clear” must a state court’s alleged mistake be? The answer to that is unclear. But it is clear that Kavanaugh rejects the longstanding rule that he and his fellow federal justices must always defer to state supreme courts on questions of state law.

That position could also have profound implications. In 2018, for example, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down gerrymandered maps drawn by the GOP-controlled state legislature. Kavanaugh’s position would allow the Republican-controlled Supreme Court of the United States to overrule such a decision.

Kavanaugh also lifts much of his reasoning from a disreputable source. Before today, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore (2000), which effectively handed the presidency to George W. Bush, had only been cited once in a Supreme Court opinion — and that one citation appeared in a footnote to a dissenting opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas, which was joined by no other justice.

But Kavanaugh quotes heavily from Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s concurring opinion in Bush, which also embraced an excessively literal approach to the word “legislature.” It appears that Bush v. Gore, arguably the most partisan decision in the Court’s history — and one that Kavanaugh helped litigate — is back in favor with key members of the Court.

It’s worth noting that the decision in Democratic National Committee was handed down literally as the Senate was voting to confirm incoming Justice Amy Coney Barrett, a staunch conservative who during her confirmation hearings would not commit to recusing herself from cases involving the 2020 election.

That means that last week’s decision allowing a Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision to stand could be very short-lived. That decision, after all, was 4-4, with Chief Justice John Roberts voting with the Court’s three liberals. With Barrett, the Court’s right flank may well be getting a fifth vote to toss out the state supreme court’s decision — and to order an unknown number of ballots tossed out in the process.

It’s unclear what immediate impact the decision in Democratic National Committee will have on the upcoming election. Last April, about 79,000 ballots arrived late during Wisconsin’s primary election but were counted anyway due to a lower court decision. The Supreme Court’s decision in Democratic National Committee will prevent similarly late ballots from being counted during the 2020 general election. The deadline for Wisconsin mail-in ballots to arrive is 8 pm on Election Day.

Though 79,000 ballots could easily swing an election, that’s only if it is close (in 2016, Trump won the state by a razor-thin margin of some 22,000 votes). A large enough margin could minimize the impact of the Court’s decision, and voters can ensure that their vote is counted by voting early enough.

But while this decision may not change the result of the 2020 election, its impact is still likely to be felt for years or even decades — assuming that Republicans retain their 6-3 majority on the Supreme Court. American election law has entered a chaotic new world, one where even the most basic rules are seemingly up for grabs. And the Supreme Court just sent a fairly clear signal that it may be about to light one of the most well-established rules on fire.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

The United States is in the middle of one of the most consequential presidential elections of our lifetimes. It’s essential that all Americans are able to access clear, concise information on what the outcome of the election could mean for their lives, and the lives of their families and communities. That is our mission at Vox. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone understand this presidential election: Contribute today from as little as $3.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/31Npk2X