Former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang sits down with Vox’s Ezra Klein to discuss universal basic income, the coronavirus, and his next job in politics. | Courtesy of Andrew Yang

Former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang sits down with Vox’s Ezra Klein to discuss universal basic income, the coronavirus, and his next job in politics. | Courtesy of Andrew Yang

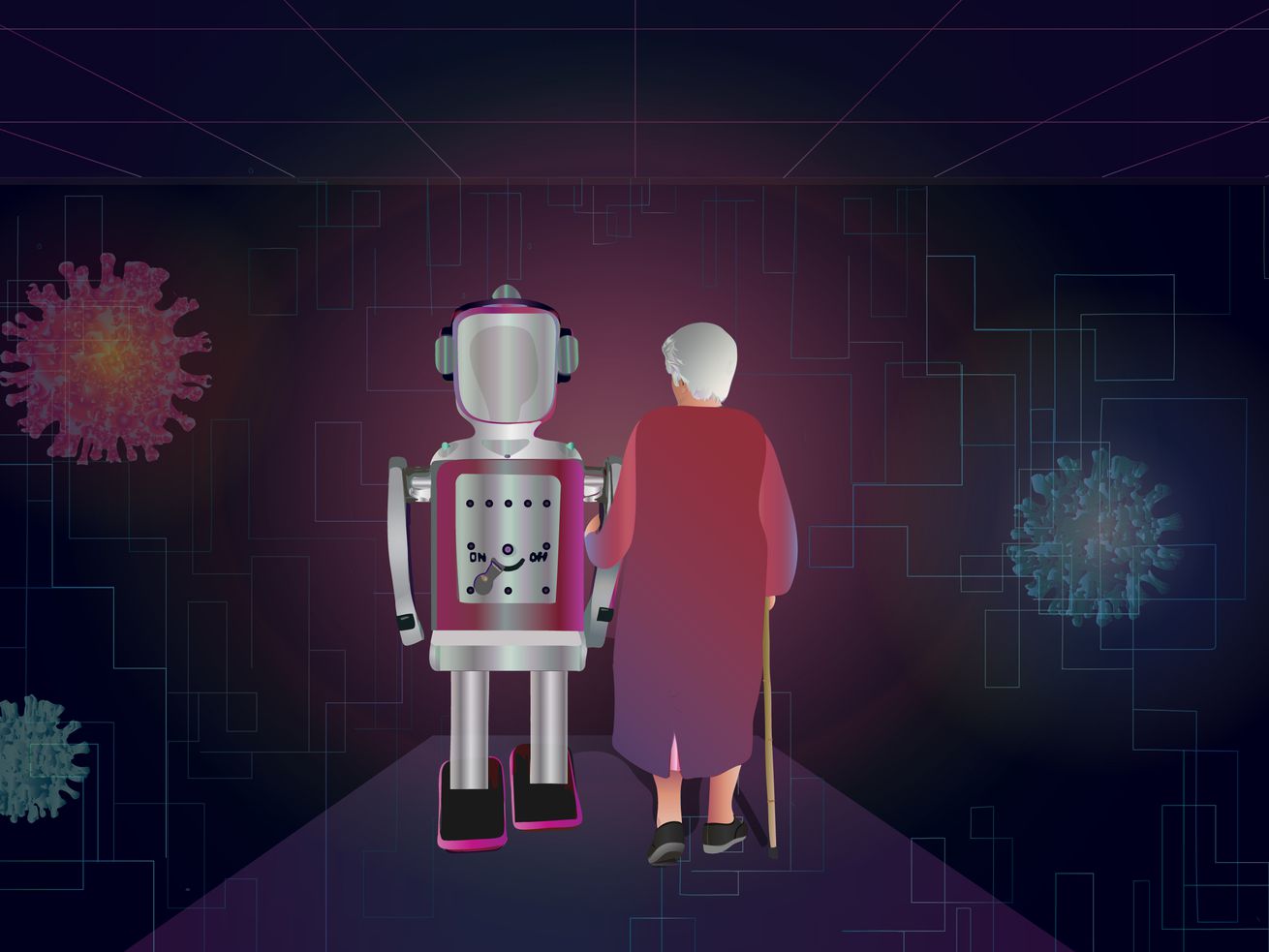

The former presidential candidate discusses universal basic income, artificial intelligence, and his next job in politics.

The last time Andrew Yang was on The Ezra Klein Show, he was just beginning his long-shot campaign for the presidency. Now, he’s fresh off a speaking slot at the Democratic National Convention and, as he reveals in this episode, talking to Joe Biden about a very specific role in a Biden administration.

Which is all to say: A lot has changed for Andrew Yang in the past few years. And even more has changed in the world. So I asked Yang back on the show to talk through this new world and his possible role in it.

We discuss how a universal basic income could shape the way we rebuild our economy, why Democrats need to take technological change more seriously, how Covid-19 has accelerated job automation, what it would take to make government actually work for people, why Yang is worried about a possible Cold War with China, and much more.

A transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows. The full conversation can be heard on The Ezra Klein Show.

Ezra Klein

When you began your presidential campaign, I understood it as a campaign based on ideas that you thought should be in the national conversation and weren’t. And then what surprised me about the way it played out was how much it emphasized an approach to politics, a way of talking to each other, a way of talking about each other that felt different. And that really resonated with people. What values were missing in politics that you felt able to bring to the race?

Andrew Yang

When I showed up on the scene, I thought I would be perceived as being to the left of Bernie, because even Bernie didn’t go so far as to talk about giving everyone money. I used to joke that I was going to be like Bernie but younger and more Asian. But that’s not how I was received at all. I was received as this realignment-type figure who was talking in terms that other candidates were not.

What’s funny for me is, it was just the way I communicate. I was arguing from facts and figures. It was my concern about the fact that we eliminated 5 million manufacturing jobs — 4 million due to automation — primarily in the swing states that decided the 2016 election. And by talking the way I talk, it ended up being a different approach to politics that some people got excited about.

That was something I did not anticipate. I learned that there are a lot of people that do want us to approach politics in a different way than we have been over the last number of years.

Ezra Klein

But there are plenty of other facts and figures candidates, like Elizabeth Warren. You talked about Bernie Sanders and imagined yourself to the left of him, but ideology is only one way people experience politics. They also experience it on the axis of how confrontational you are. You have a pretty left policy agenda, but your approach to politics isn’t nearly as confrontational. You would talk to people Democrats would rarely talk to and go on programs they would rarely go on. You really never seemed to dislike anybody on the campaign trail. Even now, on Twitter, I think you cultivate a very nice persona in a very not-so-nice space.

I’d like to hear a bit about how you think about that. It seemed to have more power than I would have expected.

Andrew Yang

I hadn’t thought of it in those terms. It’s the case that I like most Americans. I naturally don’t get angry at people that disagree with me. I kind of expect a degree of political asynchrony, because it’s not like someone’s gonna believe everything you believe.

I think people have gotten driven into different corners and pitted against each other in a way that’s unproductive. One of the things that I did find running for president was that the media would often try and goad me into conflicts: “This person said this, what do you think about that?”

The dynamic was supposed to foment an expression of outrage. I think that the outrage cycle is very negative. And I think a lot of Americans, including me, are very tired of it.

Ezra Klein

I think it also reflects the media you came up through. When most Democrats run for president, they think about getting coverage on MSNBC and liberal publications, which tend to reward a more confrontational approach.

But when you came up, you did Joe Rogan’s podcast, Sam Harris’s podcast, a lot of YouTube-world things. That’s a more mixed space — those are different worlds where people have different political concerns. Some of these folks on YouTube are able to command audiences in the millions that rival the cable networks. But it doesn’t have the mainstream establishment respect that a cable network does, so it gets ignored even though it’s no worse a way to reach people.

How much do you think the Democratic Party, or just politicians in general, are leaving on the table by not pursuing those avenues?

Andrew Yang

This is something we should talk about more. The shifting media landscape is going to impact politics very dramatically, and some folks are going to be late to it.

If you look at the cable news audiences, you’re looking at low millions — and it tends to be the same 2 million people over and over again. The cable newscasts then drive this media-narrative bubble that then gets self-reinforcing. Everyone looks out and says, “Aren’t you concerned about whatever the heck we were concerned about yesterday?” And meanwhile, like, they’re just listening to Joe Rogan or whoever and getting a very different perspective. They are hearing about issues that are more relevant to them.

The biggest example of that on the trail was impeachment. I don’t think I got a single question about impeachment the entire time, and this was when [Trump] was actually getting impeached. So there are different conversations happening. It would be very beneficial for politicians generally, but Democrats in particular, to start trying to broaden their universe.

Ezra Klein

But you obviously had to get on all these other big shows. Joe Rogan has a lot of choice in guests, and not everyone who wants to be on his program gets the invite. What always struck me as significant about your campaign is it had a very different ordinal ranking of priorities. Washington politics has developed a set of things that it considers the questions of the day, the week, the month, the year, which include things like taxes and impeachment and health care. And those are important. I cover them all the time. But it’s not the only set of things people care about. So you have these other communities that are very ill-served in the debate.

There’s this whole world that is very focused on AI risk, for example. And when you came up and wanted to move that issue up on the political agenda, there was a world of people who were receptive to that because they were already having that conversation.

Andrew Yang

That’s right. If you talk to techies, they’re much more concerned about AI. And the central argument of my campaign was around automation. A lot of Americans were happy to talk to a political figure who is talking about something that they’d been thinking about for months or years.

One of the funny byproducts of it all was that I ended up having conversations with people that didn’t feel terribly political. Because of that, I ended up reaching audiences that generally did not consider themselves political, and hopefully, I broadened the range of concerns that we should be looking at as a country.

Could a universal basic income be the way we rebuild a fairer economy post-coronavirus?

Ezra Klein

One of the things that I think politics systematically underrates in importance is technological change. We functionally live in a gerontocracy. I think Nancy Pelosi is 80. Trump is 74. Joe Biden is 77. Mitch McConnell is 78. This is not the most technologically sophisticated group you could possibly imagine. And so a lot of what is changing in technology gets underplayed.

So let’s move the conversation to AI. How has your thinking changed on it in the past few years?

Andrew Yang

A lot of the things I was concerned about have now come into full view because of the pandemic. Companies that were considering investing in AI and robot meatpackers, robot cleaners, robot grocery store clerks, and the rest of it are accelerating those investments. If you get a Domino’s Pizza from a self-driving car, you’re excited because it means less human contact, whereas before it seemed a little bit creepy. Same with the self-checkout aisle. There’s this new release that now can do a lot of writing and basic summaries on a level that’s indistinguishable from human journalists.

And two years ago, if you’d asked me, hey, is software going to get to this point? I would have said yes. But then you could still argue over it. And now, two years later, it’s here. You can see the commercial potential of this technology.

One of the reasons why I was so concerned about the impact of AI on our labor force as well is that I know how many, frankly, inefficient jobs there are in a lot of these major companies. If you gobble up another company and you have two different systems, you might keep dozens, even hundreds of folks around just to keep the systems talking to each other. A lot of our work is more replaceable than we like to think. And what’s funny is if you ask Americans about this, they will actually say a majority of other people’s jobs are automatable and subject to technological replacement. And then if you ask them about their own job, the vast majority will say, not my job. You know, that’s just the way we’re wired.

Ezra Klein

I have some slightly different views on how many jobs are automatable and what the coronavirus is going to do to the desire for human contact, but something I do think is true is we are going to see a bunch of jobs get automated in the near future as people need to find ways to do things with less human contact.

This moment is a very deep reminder that people don’t have control over their economic fortunes — that all of a sudden, a pandemic or some technological advance could happen in your industry that lays you off or that destroys the economy in your town.

So there’s been a lot of movement toward just giving people money during this pandemic. That’s not how we’ve done things during past crises. So I’d like to hear you talk a little bit about why you think that’s happened, and what you think we can learn from its performance so far.

Andrew Yang

It’s just common sense now. When you look around and you see that there are tens of millions of Americans who’ve gotten shoved out of the labor force by no fault of their own, then cash relief is the only sensible solution.

The $1,200 going out had a really positive effect on many households and on propping up our economy. But we need to make that regular, recurring, predictable. We’ve been living off of the first CARES Act, but now that benefits have [lapsed], you’re going to see distress and disintegration pick up in many households and communities. And there really is no feasible way to help so many households manage this except for direct cash relief.

Last I saw, 76 percent of Americans are pro-cash relief during the pandemic. And 55 percent are now pro-universal basic income. So it’s no longer the magical Asian man making this case. The majority of Americans realize it’s common sense and something we need to do.

Ezra Klein

There’s a big jump between using cash transfer for relief and moving to a basic income floor. And the argument against a basic income is the same one Republicans are now making when it comes to opposing extending the expanded unemployment insurance: If people can get paid and can support themselves in their lives without working, they won’t work. What is your response to them?

Andrew Yang

I think that argument is really out of date. It harkens back to some 1970s or ’80s notion of employment where if you work for a company, they’ll treat you right and give you benefits, and you’ll be able to live a fine middle-class life. We’re now living in an era when most of the jobs that have been created are gig and contract and temp jobs that don’t have benefits. In many cases, it also doesn’t include caregivers and stay-at-home parents like my wife, who has been at home for a while, in part because one of our boys is autistic and was very much in need of her time.

So to me, this is not an argument that liberals and progressives should fall for. I 100 percent agree with the statement that if you’re working full-time in the United States of America, you should not be poor. But I also think that my wife works harder than I do most every single day. And there are moms around the country [who are] in the same boat, and they should not be poor either.

Trying to define work as this anachronistic “show up to an office or factory 40 hours a week” is missing the evolution of our economy that’s been happening for decades.

Ezra Klein

Why UBI rather than the negative income tax?

Andrew Yang

I am a huge fan of a negative income tax, but I prefer a UBI for multiple reasons. It lowers the administrative burden because you don’t need to figure out how much I made last year. It removes any strange shenanigans in terms of trying to report a low income. It alleviates a payments timing issue — you’re not likely to get your negative income tax when you might need it. And politically, I think it’s more appealing to be able to say to everyone: You have intrinsic value. This is how much you get for being an American, [a] human being.

But I would be thrilled with a negative income tax if that’s where we wound up. If you can alleviate and eradicate poverty, I am all for it.

Ezra Klein

Do you think the US government has a spending constraint on it? Could we do a UBI and a Green New Deal and Medicare-for-all and just put it on the national credit card? Or do we have limited resources, and we have to make choices between them?

Andrew Yang

The biggest winners in the 21st-century economy are paying zero or near-zero in taxes very often. And if you harness the gains from the Amazons and Apples and Netflixes of the world, then you have a lot more revenue to work with very quickly. And then if you put that money into people’s hands, that money does not disappear. It ends up going right back into the local economy, in the form of car repairs and day care expenses and the occasional meal out. And those businesses all then create more opportunities and can create virtuous cycles that help end up creating jobs and human well-being.

Ezra Klein

I agree with you on that, but even if we did everything progressives have proposed in terms of taxing the rich more, it couldn’t come near paying for Medicare-for-all, UBI, and a Green New Deal. So the question is: Should we raise taxes more broadly? Or do you think there’s some value to the Modern Monetary Theory argument, that maybe we don’t need to figure out how to pay for it?

Andrew Yang

I’ve seen the math. I know the price tags on some of the things we’re talking about. But what is the cost of not addressing climate change? Climate change is going to cost us trillions of dollars and thousands of human lives if we were to do nothing. The cost of inaction is in the trillions.

So the way I’d answer your question is to say that we should not be thinking we can just do everything under the sun and put it on the government’s bottom line. But we can be much, much more aggressive than we currently are about making large-scale investments in our own future, in our infrastructure, addressing climate change and putting universal basic income into our hands. Because in many cases, these investments will end up paying us back in both human ways and economic ways.

Ezra Klein

That actually gets to the core of the series on remobilizing the economy that this podcast is a part of. As the potential Joe Biden administration thinks about what to do first, there is going to be a tension between the government trying to remobilize the economy toward a given purpose, say, a Green New Deal on climate change, or mobilize around getting money into people’s hands to create a demand-side stimulus. As somebody who has been in the UBI game for a long time but also takes climate change seriously, what would you like to see happen first?

Andrew Yang

I think we should be investing in people immediately because I’m terrified as to what’s happening in households and families around the country right now. It’s a stressful time for me and Evelyn and my kids, and we’re very fortunate. If you look at the mental health statistics right now, they’re staggering in terms of depression and use of the Crisis Text Line — there’s a lot of pain right now. So the first thing we have to do is make sure people can put food on the table and keep a roof over their head, and not have mass evictions and the rest of it.

But those are temporary measures. I think the emphasis has to be jobs, jobs, jobs. And you can get a lot of stuff done while you’re just talking about jobs. You can put cash into people’s hands and say this will be good for local businesses, which it will be. You can hire thousands of people to go to our forest lands and start actually trying to manage the tinderbox that a lot of our forests have become.

We just need to create jobs in any way we can. The labor market is in such a disastrous condition. And so if you can tie that to infrastructure, solar panels, Green New Deal, things that help us modernize, then I am all for it. But you shouldn’t stop there. If there is anything we can do to get people into some kind of productive mindset or environment, then we should just do it. And this is one thing where I think it’s very time-sensitive. I’m hopeful that Joe and Kamala decide to go big immediately.

Why Democrats need to care a lot more about making government work

Ezra Klein

One of the things that has often appealed to people about UBI and cash transfer in general, I think, is that it is a way of getting around the inefficiencies and lack of capacity of the state. We saw this with the rollout of Obamacare, for instance, and more recently with how much trouble state governments are having with unemployment insurance. Meanwhile, Social Security is a cash-transfer program that works really well.

I’m curious how you think about the problem of the deep lack of trust Americans often have in the federal government to do hard things. How should a Democratic administration think about and address that fundamental failure and political problem?

Andrew Yang

This was a big element of my pitch to folks. A lot of people are not that confident in our government’s ability to deliver value in a way that you’ll actually feel and be able to utilize every single day. But if it’s in the form of cash in your hands, then you’ll be able to utilize it in a way that benefits you the most. You solve your own problems.

There are a lot of folks who were not traditional Democrats who are very sympathetic to that line of thought, which I happen to believe and agree with. If you’re a Democrat and progressive, which I consider myself, you have to have ambition as to what government can do but also a sense of reality as to how government can deliver that value to folks.

And if the government puts cash into people’s hands, it’s going to produce so much increased confidence in government among Americans, where you can look up and say: The government got this right — this cash helped me a lot. Instead of me just telling them about it, it’s something that they’ll see in their bank account every month. It’s just a very different experience that I think can actually bring the country together in a powerful way.

Ezra Klein

I take the point you’re making here about a policy feedback cycle where, say, a relief payment creates a sense that the government can actually help you. And so you should trust the government to do more, and maybe you build up the ladder that way. But I also just wish I heard more from Democrats in power about how you’re actually going to make the government work.

In my experience, Democrats actually give very little thought to the capacity of the state to accomplish their goals: the way the federal government is structured, the way elections happen, but then also within the government itself, how procurement works, how regulatory feedback works. I think that progressives overestimate how well the government is actually working right now, or at least how well it would work if they controlled it.

We’ve gotten so trapped in this “government good or bad” argument that you end up having a lot less focus than we need on how the government works and what you do when it’s not working. How do you fix that?

Andrew Yang

I cannot tell you how much I agree with what you just said. It is so important. There’s this entire “government good, government bad” argument. And instead, what Americans hunger for is smart, effective government. We can see that government has become less effective, certainly at the congressional level, very obviously, but also in other aspects. And no one’s having the right conversation around that. I am 100 percent with you, and I’ve been thinking about the exact same thing.

Ezra Klein

This is why it infuriates me to see Democrats so lackadaisical on the filibuster, although this seems to be changing now. Because what you’re basically saying is that you are more concerned about esoteric, unbelievably misused rules of the Senate than about addressing all these crises — many of them literally life and death — that you’ve promised people you’ll do something about.

There was this piece by venture capitalist Marc Andreessen awhile back called “It’s Time to Build.” And I wrote a response to it, which argues that a lot of why we can’t build is that the government and institutions can’t operate.

I am really struck by how much elected Democrats do not believe what they say on the campaign trail. They do not believe that the problems they are facing are as bad as they say on the stump. And I’m talking here mainly about Senate Democrats, because if they did believe things were as bad as they say, they would get rid of the filibuster and do other things to make government work better.

Andrew Yang

Ezra, this is my new mission in life, which is to try and fix the mechanics of our government so it can actually deliver to us. When I ran for president, I kept getting goaded into making these very grand statements. And I had this reflection, where I thought: What’s the point of making these arguments if you’re accepting a government that can’t deliver on them anyway?

And so you need to get rid of the filibuster. You need to have the operating system of government get refreshed and updated. I’m for term limits in part for this reason. I’m very, very passionate now about trying to actually get in and fix the mechanics so that our government can function.

Ezra Klein

I’m not a term-limits fan, but I think what you’re saying in general here is really important. I remember watching 2020 Democratic presidential debates, and just thinking — as people argued this Medicare-for-all plan or that Medicare-for-most plan, or this gun control plan that won’t pass or that gun control plan that won’t pass — that it was just a fantasyland debate. It let people off the hook for how they’d do any of it. All they had to say was what they supported in theory.

The two questions that matter most, assuming Democrats win the White House, are: Did Democrats win Congress? And did Senate Democrats do something about the filibuster? And if the answer to either of those questions was no, then virtually everything else they talked about was gone.

Andrew Yang

It seemed like a bizarre theater performance. And this is from someone who was part of it.

Let’s get real, stop playing in fantasyland, and say, what can we actually get done? What are the rules we need to change to get it done? Who do we need? Because so much of our politics is degenerating into value statements.

The main problem I want to solve is that people are poor for no reason, and I believe that if we change that, we’d change a lot of other things very positively — including, I believe, our fractured politics, at least in some measure. But if you have a filibuster, it doesn’t matter if I change a couple seats here and there. You’re never gonna get to a threshold where you can pass over the filibuster.

There’s nothing in the Constitution about a filibuster. It is just some weird, arcane, esoteric Senate rule that took on a life of its own. And so if you’re willing to put that rule above getting stuff done, then what are you doing?

Why Democrats need a more robust theory of technological change

Ezra Klein

While we’re talking about the Democratic debates, I appreciated how you would inject questions about technology into them. You often would do this when it came to climate change, talking about things like fourth generation nuclear.

I’ve realized that a lot of the problems that I care most about solving have a huge technological dimension to them. I care about animal suffering, and by far, the most promising way to do something about that is plant- and cell-based meat. I’ve had Saul Griffith on the show talking about how we could fix climate change without any new technology being invented, but there’s just no doubt it would become a lot easier if we can invent some great new stuff. Artificial intelligence often gets talked about in a dystopic way, but if we really could invent it, it could make life pretty amazing. Better technologies in how we fight cancer, and gene therapies and other things, could make our health care system much better.

Something that has struck me is that I don’t think progressives have much of a theory of technology anymore. It’s often talked about in this dystopic way. I often felt you oscillated between a very scary story about AI and then also a real interest in technology as a way of solving problems. What do you think the political orientation to technology in general should be?

Andrew Yang

I think that ideally, progressives are for progress. What is going to enable a ton of progress is technology.

One of the fun things about my campaign was I was making some very dark arguments about the impact of technology, which I completely believe. But I also agree with you that if you’re trying to make people smarter, healthier, mentally healthier, or you’re trying to clean up our planet or feed people in a way that doesn’t brutalize animals, technology is a part of every single one of those solutions in a very central way.

One of the dangers, to me, about a lot of our politics now is we’re each arguing for different brands of nostalgia. Meanwhile, time only goes in one direction.

When you go to some of the folks in California who are working on the future, some of the things that they’re working on are very positive and inspirational. Some of them are very depressing and dystopian. But they’re all packaged together. We should not be a group of people or a party that also has our heads in the sand about the positive and negative changes that technology brings. We have to be the party that is hard-nosed and realistic, but also willing to embrace the technologies that could lead us to something that more closely resembles utopia than this current mess we’re living.

So I completely agree. We need to be embracing these technologies at a much higher level. And I may be a part of that in this next administration, if we succeed in getting Trump out of the way.

Ezra Klein

I want to follow up on that tantalizing “I may be a part of that.” Is there a job you’ve been talking about?

Andrew Yang

I’ve had some very general, informal conversations with the Biden camp about trying to take on some sort of technology-facing role, involving some of the concerns that I campaigned on and trying to address them. One thing we haven’t talked about but I’m very passionate about is the effect of social media and technology on our kids’ mental health.

Right now you have massive levels of anxiety and depression among teenage girls in particular in order to make certain companies like Facebook richer, which is not a good look. But our government is way behind the curve on these issues. I’ve offered my help in trying to catch us up, and there’s some interest in taking me up on that.

Ezra Klein

A minute ago, you talked about how some of the technology people in Silicon Valley are working on is very utopian, and some of it is very dystopian. And what always strikes me is that the way that plays out, in most cases, is not intrinsic to the technology. Oftentimes it is actually about the way markets, rules, regulations, but also to some degree government implementation, taxation etc. is going to interface with technology that determines whether it ends up being utopian or dystopian.

So there seems to me to be a more obvious approach here, which is for both parties to use the government as a research and innovation accelerant. But then it also has to be a more central priority for the government to have views and to care about how technology is rolled out, who has access to it, and also what rules it operates under.

AI is the most obvious example, just given the size of its potential impact. But we could also put a lot of money into drug development, which we already do, and then insist on very different rules for how patents work and how quickly things move to generic. One of my favorite Bernie Sanders health care policies, going way back in his Senate career, is his idea to create prizes of, say, $5 billion to create a drug that cures X problem. And then if you do it, you’ll get the $5 billion and the drug is generic from the minute it goes forward.

Andrew Yang

That is spot on. Right now our government is out to lunch on most of these technology issues, and we need to change that. This should be central for both parties because the rate of change is just getting faster and faster. We got rid of the Office of Technology Assessment in 1995.

We can all sense that — it’s embarrassing really. Everyone has this collective groan when it comes to government and technology. And that’s something that we should try and rev up and invest in meaningfully. The US Digital Service, which came about in the aftermath of HealthCare.gov, is still operating, but it’s down to something like 180 people. If you look at the scope of the federal workforce, that’s not enough. And those people are not empowered. But even within their constraints, they’re projected to save something like $600 million in government costs.

Ezra Klein

If you were helping to modernize government on technology in a future administration, where would you start? What would be the kinds of things you would imagine doing?

Andrew Yang

Ramp up the US Digital Service and empower it. You and I both know that there are hundreds, maybe even thousands, of very talented technologists, designers, coders who would help government if they had a runway to do so and felt like they could actually be empowered — as opposed to getting their hands tied in red tape and bureaucracy and the rest of it. Instead of 180, you should have 10 to 20 times that number of folks working to help implement some of the policies that folks are envisioning for us digitally. That would be step one. You take what’s been working and then you pour fuel on it.

The other thing is I think that there should be some kind of West Coast base of operation as part of the talent enlistment, because there are a lot of techies that might not want to uproot their families. Then we need to have actual experts getting into the guts of the social media companies and the apps, because each of these companies is its own thing. You can’t really have a one size fits all, like 20th-century antitrust rules. There are all of these features that are company specific — you need real expertise to try and get to the bottom of [it] and see if you can curb the worst of the excesses.

Trump’s second term and the dangers of a Cold War with China

Ezra Klein

What do you think a second Trump term would look like?

Andrew Yang

It would be catastrophic. We’re seeing the deterioration and disintegration of our way of life, and I don’t see that reversing itself under Trump. I think with Joe and Kamala, there is at least a chance that we’ll get enough of a consensus to invest trillions of dollars in jobs, infrastructure, economic relief, health care, climate change mitigation, you name it.

We have a multi-trillion-dollar hole that’s been blasted in our annual economy, and tens of millions of us have gotten pushed to the side. We have to give ourselves a chance, and we at least get our fighting chance with Joe and Kamala. So hopefully they’re our next president and vice president.

Ezra Klein

You talked a fair amount about Asian-American discrimination during the campaign, so when you listen to Trump during his convention speech, calling it the China virus and saying reelect him and he’ll make sure to make China pay, how did that strike you personally? How do you see that playing out?

Andrew Yang

I felt like it was Trump reverting to his usual playbook of distracting from his own failures. Certainly as an Asian American, it’s painful because there’s always a sense that somehow your Americanness is in question. Having Trump double down on that is really corrosive for the country, but it’s painful for Asian Americans in particular. I feel like our Americanness has been questioned to a higher degree in the wake of the coronavirus than has been the case that really any point in my memory.

Ezra Klein

When I started in politics as a journalist in the early 2000s, there was a real hunger for an external enemy, especially post-9/11. People talked about the clash of civilizations between the West and Islam. I think among politicians who are comfortable in a Cold War framework, there’s this real desire to find the new external threat.

Now, I’m not a big fan of the way China withheld information on the coronavirus, and I’m certainly not a fan of their increasing authoritarianism or their brutal treatment of the Uighurs. But I’m really scared of this idea of creating an oppositional relationship between America and China, which is something I think would be very prominent in a second Trump term.

Politicians who see their own political safety in creating an enemy and creating fear in a world where we have to actually work together on threats like pandemics is such a potentially dangerous thing. I think people’s feelings toward China’s leadership right now should be complicated, but nevertheless, very little would be as bad as a “clash of civilizations” narrative becoming the dominant foreign policy framework toward China.

Andrew Yang

I agree with you on all fronts. You and I agree on a lot of things. Who knew?

Ezra Klein

There’s too much agreement in this conversation. It’s a disaster.

Andrew Yang

I agree with you that Trump’s playbook is to find an enemy. And in this case, it’s going to naturally head toward China and the East, to disastrous consequences.

I agree it’s a very complex, fraught relationship, with some massive problems and concerns around the things you described and then some — like the theft of our intellectual property. But you need to have some kind of relationship with China in order to guard against the next pandemic, to make progress on climate change, to make progress on data concerns, to make progress on North Korea. There is a much less safe world if you aren’t in touch with the Chinese government to the point where you even can’t speak to them about something that’s happening that would concern American well-being.

That’s the reality. And unfortunately, we are getting to a point now where folks feel better served politically by trying to present a different version of reality for purposes that benefit them, their party, certain economic interests, but are really bad for all of us long term.

And to your point, too, as someone who grew up in this country, one of the simmering fears you have as an Asian American is that if you wind up with a US-China geopolitical conflict, Asian Americans will end up being caught right in the middle.

Ezra Klein

What is one way you’d like to change the Democratic Party?

Andrew Yang

I think Democrats need to figure out why it is that many working-class Americans do not feel like we are fighting for them or we stand for them. I ran into this all the time on the trail. When a waitress or a truck driver or a retail clerk found out I was a Democrat, it was like I had said a dirty word. And I thought to myself, “Shouldn’t you be who we are fighting for?” I think we’ve gotten caught in these exchanges that don’t actually feel like they’re relevant to those folks, and we need to get better at it.

Unfortunately, Republicans have become more effective at communicating to certain groups of people than we have. So instead of saying, well, it’s their fault, we should do some soul-searching: Why is it that they don’t think that we’re speaking to them?

We do not want to be characterized as the party of the educated elite or folks who just live in big cities. Because if that’s the case, then trying to reach folks that we’re going to need to reach around the country is going to be very difficult. That would be one big message I’d have. I’m obviously, like, on board with a lot of the policy prescriptions that we have. I just want to try and present them to folks in a way that makes them feel like it’s going to touch them and improve their lives every single day.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work, and helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world. Contribute today from as little as $3.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2ZkMfS2

A bilingual sign stands outside a polling center at a public library on April 28, 2013, in Austin, Texas. | John Moore/Getty Images

A bilingual sign stands outside a polling center at a public library on April 28, 2013, in Austin, Texas. | John Moore/Getty Images

Former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang sits down with Vox’s Ezra Klein to discuss universal basic income, the coronavirus, and his next job in politics. | Courtesy of Andrew Yang

Former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang sits down with Vox’s Ezra Klein to discuss universal basic income, the coronavirus, and his next job in politics. | Courtesy of Andrew Yang

Efi Chalikopoulou for Vox

Efi Chalikopoulou for Vox

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21864789/GettyImages_636182984.jpg) BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21864825/GettyImages_543742084.jpg) Yamaguchi Haruyoshi/Corbis via Getty Images

Yamaguchi Haruyoshi/Corbis via Getty Images

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21864874/GettyImages_501921914.jpg) Laura Lezza/Getty Images

Laura Lezza/Getty Images

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21864893/GettyImages_1066094076.jpg) Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images

Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images